Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery (MIS)

Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery (MIS)

Minimally invasive spine surgery (MIS) was first performed in the 1980s, but has recently seen rapid advances. Technological advances have enabled spine surgeons to expand patient selection and treat an evolving array of spinal disorders, such as degenerative disc disease, herniated disc, fractures, tumors, infections, instability, and deformity.

MIS was developed to treat disorders of the spine with less disruption to the muscles. This can result in quicker recovery, decrease operative blood loss, and speed patient return to normal function. In some MIS approaches, also called “keyhole surgeries,” surgeons use a tiny endoscope with a camera on the end, which is inserted through a small incision in the skin. The camera provides surgeons with an inside view, enabling surgical access to the affected area of the spine.

Not all patients are appropriate candidates for MIS procedures. It is important to keep in mind that there needs to be certainty that the same or better results can be achieved through MIS techniques as with the respective open procedure.

MIS procedures can be performed on an outpatient basis but most require a hospital stay, typically less than 24 hours to 2 days, depending on the procedure.

Benefits:

The potential benefits of MIS include:

- Smaller incisions

- Smaller scars/less scar tissue

- Reduced blood loss

- Less pain

- Less soft tissue damage

- Reduced muscle retraction

- Decreased postoperative narcotics

- Shorter hospital stay

- Possibility of performing on outpatient basis

- Faster recovery

- Quicker return to work and activities

Surgery Risks:

As with any spinal surgical procedure, there are routine risks.

Conditions Treated using MIS Procedures

- Degenerative disc disease

- Herniated disc

- Lumbar spinal stenosis

- Spinal deformities such as scoliosis

- Spinal infections

- Spinal instability

- Vertebral compression fractures

Glossary of Select Spine-Related Surgical Terms

Bone spur: bony growth or rough edges of bone.

Decompression: a surgical procedure performed to relieve pressure and alleviate pain caused by the impingement of bone and/or disc material on the spinal cord or nerves.

Disc degeneration: degeneration or wearing out of a disc. A disc in the spine may deteriorate or wear out over time. A deteriorated disc may or may not cause pain.

Discectomy: the surgical removal of part or all of an intervertebral disc, performed to relieve pressure on a nerve root or the spinal cord.

Excision: removal by cutting away material, as in removing a disc.

Facet: a posterior structure of a vertebra which articulates (joins) with a facet of an adjacent vertebra to form a facet joint that allows motion in the spinal column. Each vertebra has a right and left superior (upper) facet and a right and left inferior (lower) facet.

Foramen: a normal occurring opening or passage in the vertebrae of the spine through which the spinal nerve roots travel.

Foraminotomy: surgical opening or enlargement of the bony opening traversed by a nerve root as it leaves the spinal canal, to help increase space over a nerve canal. This surgery can be done alone or together with a laminotomy.

Herniated disc: a condition, also known as a slipped or ruptured disc, in which the gelatinous core material of a disc bulges out of position and puts painful pressure on surrounding nerve roots.

Intervertebral foramen: An opening between vertebrae through which nerves leave the spine and extend to other parts of the body. Also known as neural foramen.

Kyphosis: a condition in which the upper back curves forward, sometimes leading to the appearance of a hump in the back. Kyphosis may result from years of poor posture, spine fractures associated with osteoporosis, trauma, or developmental problems.

Lamina: the flattened or arched part of the vertebral arch, forming the roof of the spinal canal.

Laminectomy: surgical removal of the rear part of a vertebra in order to gain access to the spinal cord or nerve roots, to remove tumors, to treat injuries to the spine, or to relieve pressure on a nerve root.

Laminotomy: an opening made in a lamina, to relieve pressure on the nerve roots.

Lordosis: Lordotic curves refer to the inward curve of the lumbar spine. In some patients, this may represent a spinal deformity, also called swayback, which occurs when the lower back curves inward more than normal. Pathologic or excessive lordosis may be caused by osteoporosis or spondylolisthesis. Obesity, congenital disorders, or overcompensation for kyphosis may contribute to this condition.

Medial facetectomy: a procedure in which a part of the facet is removed to increase space in the spinal canal.

Nerve roots: the initial portion of a spinal nerve; the nerve root is an extension of the central nervous system that begins at the spinal canal and ends in the extremities (fingers, toes). Its purpose is to send sensory information from the extremity to the brain, and a motor commands from the brain to the extremity.

Pedicle: the bony part of each side of the neural arch of a vertebra that connects the lamina (back part) with the vertebral body (front part).

Percutaneous: effected, occurring, or performed through the skin.

Pseudoarthrosis: the movement of a bone at the location of a fracture or a fusion resulting from inadequate healing of the fracture or failure of the fusion to mature properly. This can also result from a developmental failure.

Scoliosis: lateral (sideways) curvature of the spine.

Spinal stenosis: abnormal narrowing of the vertebral column that may result in pressure on the spinal cord, spinal sac, or nerve roots arising from the spinal cord.

Spinous process: a slender projection of bone from the back of a vertebra to which muscles and ligaments are attached.

Spondylitis: inflammation of vertebrae.

Spondylolisthesis: the forward displacement of one vertebra on another.

Spondylosis: degenerative bone changes in the spine, most commonly affecting the vertebral joints.

Device Technology

Endoscope: a thin, fiber optic tube with a light and lens, used to examine the interior of the patient‘s body; provides minimally invasive access for diagnostic and surgical procedures. Currently only a small number of spinal surgeries can be performed utilizing an endoscopic approach.

Fluoroscope: an imaging device that uses x-rays to view internal body structures on a screen, intraoperatively.

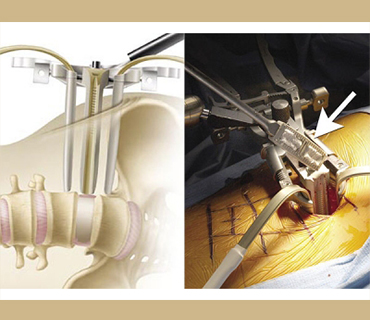

Minimally invasive tubular retractor (MITR): muscle-splitting technology first introduced in 1995 in conjunction with microendoscopic discectomy. The tubular retractor is used to create a tunnel down to the spinal column, and measures 1.6 cm in diameter (about 1/2 of an inch). The actual skin incision is a little larger, but is generally about 2.5 cm in length. A “muscle splitting” approach is employed, in which the tubular retractor is passed through a tunnel in the muscles of the back, rather than stripping the muscles away from the spine, as is done in open procedures. This approach limits damage to the muscles around the spine and decreases blood loss during surgery.

Portals: devices that provide a passage through which the surgeon operates. After the incision is made, dilators are used to reach the area of the spine that the surgeon is working on. Fluoroscopy is used to locate the right level at time of surgery. During the procedure, instruments are used to continue the dissection through the portal. When the portal is removed, all the tissue falls back into place. In order to avoid damaging the tissue by moving instruments in and out of the passage, the portal or tubular retractor is placed into the incision to hold the tissue apart and left in place throughout the procedure. There are open and sealed portals. The portals used in the thoracic spine are usually 11 to 12 mm, while portals used in the abdominal cavity tend to be larger. All of the instruments and implants must be designed to fit through these small passages and perform surgical functions once they reach the site.

Creating the Operating Space

In the thoracic spine, the lung is deflated to provide operating space. The anesthesiologist places a special breathing tube down the trachea into the large airway of each lung. The patient is under general anesthesia and breathing with only one lung, which is considered very safe and a common practice. This allows the opposite lung to deflate and falls out of the way of the spine. The portals are placed and the spinal procedure is begun.

Spinal Fusion :

Spinal fusion is an operation that creates a solid union between two or more vertebrae. This procedure may assist in strengthening and stabilizing the spine and may thereby help to alleviate severe and chronic back pain. The best clinical results are generally achieved in single-level fusion, although fusion at two levels may be performed in properly selected patients.

Almost all of the surgical treatment options for fusing the spine involve placement of a bone graft between the vertebrae. Bone grafts may be taken from the hip or from another bone in the same patient (autograft) or from a bone bank (allograft). Bone graft extenders and bone morphogenetic proteins (hormones that cause bone to grow inside the body) can also be used to reduce or eliminate the need for bone grafts.

Fusion may or may not involve use of supplemental hardware (instrumentation) such as plates, screws, and cages. This fusing of the bone graft with the bones of the spine will provide a permanent union between those bones. Once that occurs, the hardware is no longer needed, but most patients prefer to leave the hardware in place rather than go through another surgery to remove it.

Fusion can sometimes be performed via smaller incisions through MIS techniques. The use of advanced fluoroscopy and endoscopy has improved the accuracy of incisions and hardware placement, minimizing tissue trauma while enabling an MIS approach.

MIS Fusion Procedures

- Minimally Invasive Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF and DLIF)

- Minimally Invasive Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (PLIF)

- Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion (TLIF)

- Minimally Invasive Posterior Thoracic Fusion

Lumbar fusion procedures at a glance | |||

Procedure | Approach | Incision Size(s) | Surgery Duration |

XLIF and DLIF | side | 5-cm and 2.5-cm | 1 to 1 1/2 hours |

PLIF | back | two 2.5-cm | 3 to 3 1/2 hours |

TLIF | back and side | 2- to 4-cm | 2 1/2 hours |

Minimally Invasive Lateral Interbody Fusion

eXtreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF)

Direct Lateral Interbody Fusion (DLIF)

These are MIS procedures performed in patients with spinal instability caused by degenerative discs and/or facet joints that cause unnatural motion and pain, loss of height of the disc space between the vertebrae that causes pinching of the spinal nerves exiting the spinal canal, slippage of one vertebra over another, and/or changes in the normal curvature of the spine. The primary difference in these approaches is the area of the body through which the spine is accessed.

To access the anterior spine and disc space, a 5-cm incision is made on the patient’s side, usually with a second 2.5-cm incision just behind the first one. Special retractors are utilized, in addition to fluoroscopy, which provides intraoperative x-ray images of the spine. A tubular retractor or portal is passed and positioned along the lateral aspect of the vertebral bodies being operated upon. Monitoring equipment is used to determine the placement of the instruments in relationship to the spinal nerves. Disc material is removed from the spine and replaced with a bone graft, along with structural support from a cage made of bone, titanium, carbon-fiber, or a polymer. This provides extra stability and helps the bone heal. Sometimes, surgeons will position small screws in the spine posteriorly through an additional procedure. This procedure is limited to one or two levels, and only vertebra that can be clearly accessed from the side of the body can be operated on. This procedure typically takes about 1 to 1 1/2 hours to perform.

Outcome

In general, there is very little blood loss with this procedure. Many patients are ambulatory within a few hours and discharged from the hospital the next day. Patients are often back to work within a few weeks.

Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty

Vertebroplasty for the treatment of vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) was introduced in the United States in the early 1990s. The procedure is usually done on an outpatient basis, although some patients stay in the hospital overnight. The procedure may be performed with a local anesthetic and intravenous sedation or general anesthesia. Using x-ray guidance, a small needle containing specially formulated acrylic bone cement is injected into the collapsed vertebra. The cement hardens within minutes, strengthening and stabilizing the fractured vertebra. Most experts believe that pain relief is achieved through mechanical support and stability provided by the bone cement. Vertebroplasty typically takes about 1 to 2 hours to perform, depending on the number of vertebrae being treated.

A newer procedure, called kyphoplasty, involves an added procedure performed before the cement is injected into the vertebra. First, two small incisions are made and a probe is placed into the vertebral space where the fracture is located. The bone is drilled and one balloon (called a bone tamp) is inserted on each side. The two balloons are then inflated with contrast medium (which are visualized using image guidance x-rays) until they expand to the desired height and removed. The spaces created by the balloons are then filled with the cement. Kyphoplasty has the added benefit of restoring height to the spine.

Outcome

Complication rates for vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty have been estimated at less than 2 percent for osteoporotic VCFs and up to 10 percent for malignant tumor-related VCFs.