Arteriovenous Malformations

Arteriovenous Malformations

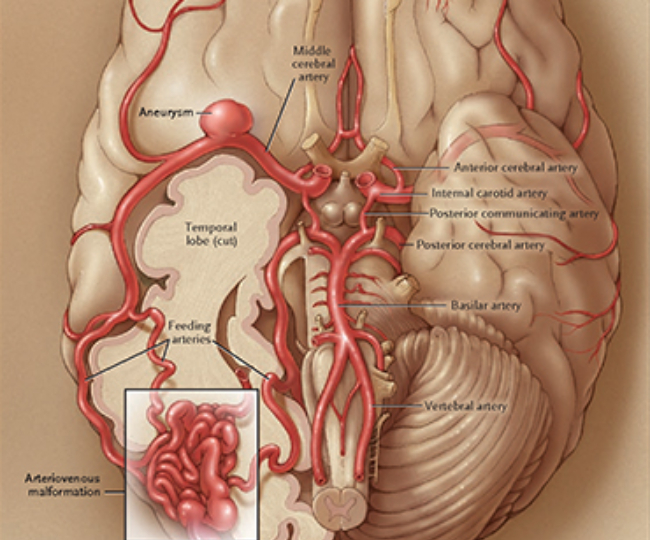

An AVM is a tangle of abnormal and poorly formed blood vessels (arteries and veins), with an innate propensity to bleed. An AVM can occur anywhere in the body, but brain and spinal AVMs present substantial risks when they bleed. Because the brain and its blood vessels are formed together during embryological development, abnormal blood vessel formation is often associated with abnormal brain tissue. Consequently, AVMs are usually associated with a focal abnormality of brain tissue, allowing them to be removed without damage to normal brain tissue.

Dural AVMs occur in the covering (dura) of the brain, and are an acquired disorder that may be triggered by an injury. AVMs can sometimes develop after a head or spine trauma, and in such cases, are often referred to as AV fistulas.

Incidence and Prevalence

- The incidence of AVM is estimated at one in 100,000.

- The prevalence of AVM is estimated at 18 in 100,000.

- An estimated two-thirds of AVMs occur before age 40.

- Every year, about four out of every 100 people with an AVM will experience a hemorrhage.

- Each hemorrhage poses a 15-20 percent risk of death or stroke, 30 percent neurological morbidity, and10 percent mortality.

- When hemorrhage occurs, it affects the following regions statistically: intracerebral (41 percent), subarachnoid (24 percent), intraventricular location (12 percent), and various combinations (23 percent).

- AVMs are the second most identifiable cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage. (SAH) after cerebral aneurysms, accounting for 10 percent of all cases of SAH.

- About 1 percent of people with AVMs will develop epileptic seizures for the first time.

Symptoms

A person with an AVM may experience no symptoms. AVMs tend to be discovered only incidentally, usually either at autopsy or during treatment for an unrelated disorder. However, about 12 percent of people with AVMs will experience symptoms, varying in severity. AVMs can irritate the surrounding brain and cause seizures or headaches. The most common symptom is brain hemorrhage. Any of the following symptoms may occur:

- Seizures, new onset

- Muscle weakness or paralysis

- Loss of coordination

- Difficulties carrying out organizational tasks

- Dizziness

- Headaches

- Visual disturbances

- Language problems

- Abnormal sensations such as numbness, tingling, or spontaneous pain

- Memory deficits

- Mental confusion

- Hallucinations

- Dementia

Diagnosis

AVMs are usually diagnosed through a combination of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and angiography. These tests may need to be repeated to analyze a change in the size of the AVM, recent bleeding, or the appearance of new lesions.

Left untreated, AVMs can enlarge and rupture, causing intracerebral hemorrhage or SAH and permanent brain damage. Deep bleeding is usually referred to as an intracerebral or parenchymal hemorrhage; bleeding within the membranes or on the surface of the brain is known as subdural hemorrhage (SDH) or SAH.

The damaging effects of a hemorrhage are related to lesion location. Bleeding from AVMs located deep inside the interior tissues, or parenchyma of the brain, generally causes more severe neurological damage than does bleeding from lesions located in the dural or pial membranes or on the surface of the brain or spinal cord. AVM location is an important factor to consider when weighing the relative risks of surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Preventing the rupture or rerupture of vascular malformations is one of the major reasons that early neurosurgical treatment is recommended for AVMs.

Treatment

A treatment plan is devised to offer the lowest risk, yet highest chance of obliterating the lesion. The three types of treatment available include direct removal using microsurgical techniques, stereotactic radiosurgery, and embolization using neuroendovascular techniques. Although microsurgical treatment affords the opportunity for immediate removal of the AVM, some AVMs may best be treated with a combination of therapies. In some patients, the AVM is monitored on a regular basis with the understanding that there may be some risk of hemorrhage or other neurological symptoms including seizures or focal deficit. This monitoring strategy depends on the subtype of AVM and cannot be used to predict when a hemorrhage may occur.

Microsurgery

Because the nature of AVM is congenital, and therefore associated in most cases with a focal abnormality of brain tissue, it may be removed with minimal disruption of normal brain tissue. This constitutes the rationale and strategy for microsurgical removal. The recommendation for surgery is typically elective, except in the case of large, life-threatening blood accumulations (hematomas) caused by bleeding of the AVM. In such cases, only superficial AVMs that are readily controllable are removed along with the hematoma. When the hematoma is caused by a complicated AVM, the blood clot can be removed and the patient given time to recover until further details are known regarding the exact nature of the AVM.

Stereotactic radiosurgery

Stereotactic radiosurgery is a minimally invasive treatment that uses computer guidance to concentrate radiation to the malformed vessels of the brain. This radiation causes abnormal vessels to close off. Unfortunately, stereotactic radiosurgery is usually limited to lesions less than 3.5 cm in diameter, and may take up to two years to completely obliterate the lesion. For this reason it is not ideally suited to AVMs that have already bled, unless they are surgically inaccessible. Because ionizing radiation is harmful to normal tissue as well as AVM vessels, it must be used judiciously.

Embolization

Endovascular embolization uses specially designed microcatheters, which are guided directly into the AVM via angiography. The lesion is blocked from the inside using the process of embolization, which occludes the abnormal blood vessels in the AVM. Although this method may be effective in reducing the size of an AVM, it is rarely able to completely eliminate it. Neuroendovascular therapy can make subsequent surgical removal of an AVM safer, or can reduce the size of an AVM to a size that may inevitably improve the outcome of stereotactic radiosurgery. This procedure is also associated with substantial risk, since the path taken by such embolic materials can be difficult to predict, and blockage of normal vessels or of the outflow of the AVM may occur. The former may result in stroke, and the latter in bleeding from the AVM. These procedures are therefore also used judiciously, and with ample clinical judgment.

Outcome

Patient outcome depends on the location of the AVM and severity of the bleeding, as well as the extent of neurological symptoms. Many patients undergoing microsurgery make an excellent and quick recovery after several days of hospitalization. Following or during surgery, an angiogram is performed to assure complete removal of the AVM. If the AVM is completely removed, the patient is considered cured. About 5-10 percent of AVMs can be obliterated (cured) using endovascular techniques alone.