Pituitary Gland And Pituitary Tumors

Pituitary Gland And Pituitary Tumors

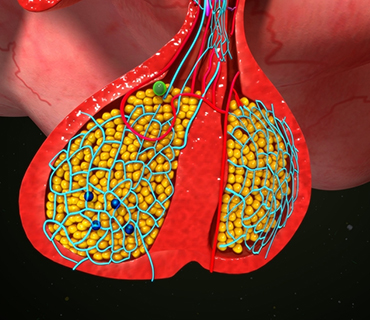

The pituitary is a small gland attached to the base of the brain (behind the nose) in an area called the pituitary fossa or sella turcica. The pituitary is often called the “master gland” because it controls the secretion of hormones. A normal pituitary gland weighs less than one gram, and is about the size and shape of a kidney bean.

The function of the pituitary can be compared to a household thermostat. The thermostat constantly measures the temperature in the house and sends signals to the heater to turn it on or off to maintain a steady, comfortable temperature. The pituitary gland constantly monitors body functions and sends signals to remote organs and glands to control their function and maintain the appropriate environment. The ideal “thermostat” setting depends on many factors such as level of activity, gender, body composition, etc.

The pituitary is responsible for controlling and coordinating the following:

- Growth and development

- The function of various body organs (i.e. kidneys, breasts and uterus)

- The function of other glands (i.e. thyroid, gonads, and adrenal glands

Pituitary Anatomy and Functions

The pituitary gland itself, is connected to and controlled by the hypothalamus, a region of the brain located right above the pituitary. The hypothalamus and pituitary together comprise the neuroendocrine system.

The anterior pituitary accounts for about 80 percent of the pituitary gland, and is composed of the anterior lobe and the intermediate zone. The anterior lobe is responsible for the majority of the signaling hormones released into the blood stream.

The posterior pituitary develops very early in life and does not produce any hormones of its own. It does contain the nerve endings of brain cells (neurons) that arise from the hypothalamus. These neurons produce the hormones vasopressin and oxytocin, which are transported down the pituitary stalk into the posterior pituitary. They are stored for later release into the bloodstream.

The pituitary and hypothalamus work together to regulate the daily functions of the body, as well as play an essential role in growth, development and reproduction.

The pituitary gland performs its key functions by releasing several signaling hormones that consequently control the activities of other organs. The pituitary produces the following hormones:

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) – ACTH triggers the adrenals to release hormones such as cortisol and aldosterone. These hormones regulate carbohydrate/protein metabolism and water/sodium balance, respectively.

Growth Hormone (GH) – This is the principal hormone that regulates metabolism and growth.

Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) – These hormones control the production of sex hormones (estrogen and testosterone).

Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone (MSH) – MSH regulates the production of melanin, a dark pigment, through melanocytes in the skin. Increased melanin production produces pigmentation or tanning of the skin. Some conditions causing excessive production of melanocyte-stimulating hormone may lead to darkening of the skin.

Prolactin (PRL) – This hormone stimulates secretion of breast milk.

Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) – TSH stimulates the thyroid gland to release thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormones control basal metabolic rate and play an important role in growth and maturation. Thyroid hormones affect almost every organ in the body.

Vasopressin, also called anti-diuretic hormone (ADH) – This hormone promotes water retention.

Pituitary Adenomas

Pituitary adenomas are the fourth most common intracranial tumor after gliomas, meningiomas and schwannomas. The large majority of pituitary adenomas are benign (not malignant) and are fairly slow growing. They more commonly affect people in their 30s or 40s, although they are diagnosed in children as well. Most of these tumors can be successfully treated. Pituitary tumors can vary in size and behavior. Tumors that produce hormones are called functioning tumors, while those that do not produce hormones are called nonfunctioning tumors.

Symptoms

Tumors smaller than 10 mm are called “microadenomas” and often secrete anterior pituitary hormones. These smaller, functional adenomas are usually detected earlier because the increased levels of hormones cause abnormal changes in the body. Approximately 50 percent of pituitary adenomas are diagnosed when they are smaller than 5 mm in size. Adenomas larger than 10 mm (the size of a dime) are called “macroadenomas,” and usually do not secrete hormones. These tumors are often discovered as they produce symptoms by compressing nearby brain or cranial nerve structures.

The symptoms of a pituitary tumor generally result from endocrine dysfunction. For example, this dysfunction can cause overproduction of growth hormones, as in acromegaly (giantism), or underproduction of growth hormones, as in hypothyroidism. Hormonal imbalances can impact fertility, menstrual periods, heat and cold tolerance, as well as affect the skin and body in other ways.

Because of the pituitary gland’s strategic location within the skull, tumors of the pituitary can compress important brain structures as they enlarge. The most common circumstance involves compression of the optic nerves, leading to a gradual loss of vision. This vision loss usually begins with a deterioration of lateral peripheral vision on both sides.

The presence of three or more of the following symptoms may indicate a pituitary tumor:

- Vision problems (blurred or double vision, drooping eyelid)

- Headaches in the forehead area

- Nausea or vomiting

- Impaired sense of smell

- Sexual dysfunction

- Depression

- Fatigue

- Infertility

- Growth problems

- Osteoporosis

- Unexplained weight gain

- Unexplained weight loss

- Easy bruising

- Aching joints

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Disrupted menses

- Early menopause

- Muscle weakness

- Galactorrhea (Spontaneous breast milk flow not associated with childbirth or the nursing of an infant)

Diagnosis

When a pituitary tumor is suspected, a physician will perform a physical examination, as well as vision testing to detect visual field deficits, such as loss of peripheral vision. Hormone testing of the blood and urine and imaging studies of the brain are used to confirm diagnosis. The most accurate diagnostic imaging test is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed with and without a contrast agent.

Treatment

Early intervention provides the best chance for cure or control of the tumor and its side effects. There are three types of treatment used for pituitary tumors: surgical removal of the tumor, radiation therapy using high-dose x-rays/proton beams to kill tumor cells, and medication therapy to shrink or eradicate the tumor.

Surgery

- The transsphenoidal approach involves making an incision in the upper gum line or nasal cavity and accessing the tumor through the base of the skull. This approach is usually the procedure of choice because it is less invasive, has fewer side effects, and patients generally recover more quickly. Patients can often leave the hospital as early as two to four days after surgery.

Endoscopy is a newer, minimally invasive approach which allows neurosurgeons to utilize a tiny endoscope with a camera on the end. A tiny endoscope inserted through the nostril is placed in front of the tumor in the sphenoid sinus, and the tumor is removed with specially designed surgical tools. Postoperative discomfort is usually minimal. Endoscopic brain surgery is another surgical option for removing pituitary adenomas, but can only be utilized in certain cases.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays to kill cancer cells and abnormal pituitary cells and shrink tumors. Radiation therapy may be an option if the tumor cannot be treated effectively through medication or surgery.

- Standard External Beam Radiotherapy uses a radiation source that is nonselective and radiates all cells in the path of the beam. The radiation path beam may damage other portions of the brain in the general area of the pituitary gland.

- Proton Beam Treatment employs a specific type of radiation in which “protons”, a form of radioactivity, are directed specifically to the pituitary gland. The advantage is that less tissue surrounding the pituitary gland incurs damage.

- Stereotactic Radiosurgery (like Gamma Knife, and Cyberknife) combines standard external beam radiotherapy with a technique that focuses the radiation through many different ports. This treatment tends to incur less damage to tissues adjacent to the pituitary gland.

Medication Therapy

Prolactinomas are the most common secreting pituitary adenoma seen clinically. In general, medical therapy is the first course of treatment in patients with a prolactinoma. About 80 percent of patients have prolactin levels restored to normal through dopamine agonist therapy. The most commonly used agents are bromocriptine or cabergoline. The size of the tumor will be reduced in the majority of patients to varying degrees, often resulting in improved vision, resolution of headaches, and restored menses and fertility in women. Bromocriptine has side effects, so is prescribed in gradual doses.

Cabergoline, an oral long-acting dopamine agonist, was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for hyperprolactinemia. The advantage is that it can be taken twice a week and generally has fewer side effects than bromocriptine. It has also been shown to be effective in patients whose prolactinomas are resistant to bromocriptine therapy.

In patients with microadenomas, dopamine agonist therapy is usually attempted first for a period of several months. If the tumors do not respond to medication therapy, then surgery is considered, and in general, the recommendation is that it is done within six months of the start of the medication therapy.

GH secreting adenomas may be treated medically by using somatostatin analog therapy. Somatostatin is a hormone that inhibits secretion of growth